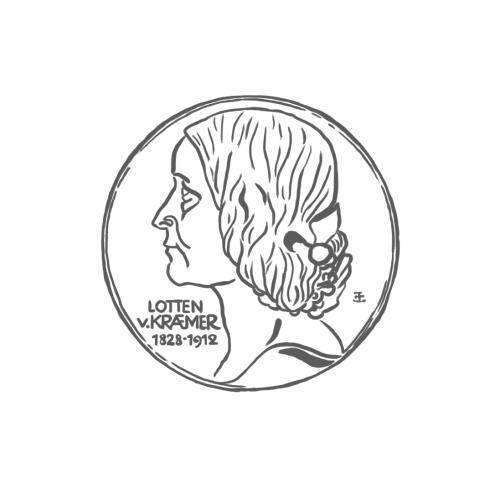

Lotten von Kræmer and The Academy of the Nine

Lotten von Kræmer

by: Anna Williams

translation: Alice E. Olsson

Today, the writer Lotten von Kræmer (1828–1912) is almost entirely forgotten. And yet she remains one of Swedish literature’s greatest benefactors. In a radical decision in her will of 1910, she chose to donate her fortune to establish a literary society with the mission to celebrate Swedish literature by presenting literary awards — a decision still honoured to this day by The Academy of the Nine.

Unique and riveting, her life story cuts straight to the conditions of women in public life during the 19th century. She wrote and travelled; was committed to literature, peace, and women’s liberation; and supported contemporary liberal reform efforts. At the same time, she wrestled with convention and laws that restricted women’s freedom of action.

Who was she then, this wealthy, forward-thinking lover of literature who, towards the end of her life, was sometimes referred to as the ‘Rag Lady’?

Lotten von Kræmer

Lotten von Kræmer was born in Stockholm on 6 August 1828 as the third child of Charlotta (née Söderberg, 1802–1869) and Robert Fredrik von Kræmer (1791–1880). Robert belonged to a noble family in Finland and moved to Sweden as a young man, where he pursued a military career. Charlotta came from a wealthy wholesale merchant family in Stockholm. They had five children: Anders Robert (1825–1903), Mathilde (1826–1907), Charlotta (‘Lotten’) (1828–1912), Gustaf (1831–1866), and Ebba (1837–1899).

In 1830, Robert von Kræmer was appointed as governor of Uppsala County and, at the age of two, Lotten moved with her family to Uppsala Castle in the university town forty miles north of Stockholm. There, her father became a zealous and successful governor who strove to modernise Uppsala. Communications were improved with new roads, the boat traffic was expanded, and parks were built. The castle also became a gathering place for the cultural elite with roots in Uppsala Romanticism — an important movement in Swedish literature with writers such as Per Daniel Amadeus Atterbom, Erik Gustaf Geijer, Thekla Knös, and Malla Silfverstolpe. Lotten met them all, attended their readings, and drew inspiration from them when she started writing in her teens.

The von Kræmer parents were keen to ensure that all of their five children receive a proper education. Young women were not yet allowed to attend university. But as the privileged children of a governor, the daughters in the family received private tuition from Uppsala academics. Lotten learned French, German, and English, and took lessons in music and drawing. They read, sang, and performed plays. The family made exciting trips to the continent; Lotten visited museums and cultural sites in Berlin, Vienna, Venice, and Paris. They spent a great deal of time at the family’s summer residences back home in Sweden: the Taxnäs Manor just outside of Uppsala and the Stenhammar Palace in Södermanland.

At the age of fourteen, Lotten contracted scarlet fever, which came to have a serious impact on the rest of her life. The disease spread to her ears, and she suffered pain, unbearable tinnitus, hissing sounds, as well as hearing loss. She tried various treatments, both from Swedish doctors and abroad, but nothing helped and her hearing got progressively worse. In the summer of 1857, she travelled with her father to Dublin to consult the famous ear doctor William Wilde, father of the two-year-old Oscar Wilde. The kind doctor did what he could, but he had no cure to offer. Nevertheless, the meeting with the Wilde family became significant for Lotten. William Wilde’s wife, Jane, was a prominent poet under the pen name Speranza — and a feminist. When Lotten took up the struggle for equality and women’s suffrage, Jane Wilde became a role model.

Seven years before the Ireland trip, another life-changing encounter had occurred. Lotten von Kræmer had just turned 22 when she first met Sten Johan Stenberg (1818–1888), ten years her senior. He was an Uppsala academic, docent (equivalent to non-tenured associate professor) of aesthetics, and part of the governor’s social circles. Lotten and Stenberg fell in love, but it would be six years before they got engaged. It happened in secret — Stenberg was a cautious man who struggled to make up his mind, both privately and professionally. Lotten had to accept keeping the relationship a secret. Both had an intense interest in literature, and when they exchanged letters they often wrote to each other in English. Perhaps they were keen to practise their language skills; but it also reinforces the cool distance that characterised at least the ever-formal Stenberg. His letters reveal little about his feelings for his fiancée. Lotten was more free-spirited and sometimes grew impatient with her strict, strait-laced fiancé.

Since an early age, Lotten von Kræmer had written poems and showed them to her older brother Robert. A poet himself, Robert became the first in a long line of merciless critics who disapproved of Lotten’s poetry. Yet that didn’t stop her. One of the traits that brought her both success and misfortune was her tenacity and ability to pick up and move on after being crushed by criticism. Now, she sent her draft poems to her fiancé, who read and commented on her work. He was not pleased. Firstly, he did not think that Lotten had a talent for poetry. Secondly, it was his firm opinion — in accordance with the prevailing views of the time — that a woman should have no part in public life, neither as a writer nor in any other capacity. Her place was in the home, taking care of her husband and children.

Lotten von Kræmer could not accept such a role. She maintained her literary aspirations and began to publish her work — which no doubt contributed to the end of their relationship. Both remained unmarried, and Sten Johan Stenberg died of a heart attack in 1888.

After the breakup, Lotten was distraught. But the 1870s turned into a productive literary decade. She did not have to worry about her finances, as she had inherited a considerable fortune and was financially independent. She covered the costs of the publication of her own books, which were published by her own press or distributed by smaller publishers and printers. In 1870, her first major poetry collection, Ackorder (‘Chords’), came out, as well as the travelogue Bland skotska berg och sjöar (‘Among Scottish mountains and lakes’). Seven years later — the same year that she permanently moved from Uppsala to Stockholm — she started her own journal, Vår Tid (‘Our time’), which ran from 1877 to 1879. In it, she contributed with her own poems, stories, and articles on contemporary issues. She advocated for social reform and took a liberal stance, calling for government intervention to address rampant prostitution and arguing for women’s suffrage and girls’ education.

With few exceptions, her poetry received disparaging criticism. She listened and felt discouraged, yet went ahead with her literary publications, which were mainly self-funded, continuing to publish poetry and drama throughout the 1880s and -90s. During her lifetime, she published a total of thirteen poetry collections, five plays, two books of prose, a travelogue, and some 80 poems in newspapers and journals. Many of them were revisions of already published material, which contributed to the stingy reception.

In the autumn of 1879, Lotten von Kræmer bought a semi-detached house on Villagatan 14 on Östermalm in Stockholm, an area where wealthy people from the upper class liked to settle. There, she lived out her days with the servant staff, becoming quite isolated due to her deafness. Lotten’s health deteriorated; she suffered from rheumatic pain, severe obsessive-compulsive disorder, and a fear of contagion. She failed to keep up her hygiene. By then, she was almost completely deaf. It was now that people began to refer to her as the ‘Rag Lady’ — the strange old woman trudging down the street in worn, dirty clothes, talking to herself. Yet with characteristic clear-sightedness, she continued her ideological work for equality and the right to vote.

As early as in the 1870s, Lotten von Kræmer had begun to draw up a will with Swedish literature as the beneficiary. In order to increase her donation, she grew more and more frugal, and the house on Villagatan fell into disrepair. She signed her final will in 1910, two years before her death. In it, she made provisions for the founding of The Academy of the Nine, which would consist of four women and four men as well as a chairperson — the latter position being held alternately by a man and by a woman. The Academy would promote Swedish literature by giving out literary prizes.

Lotten von Kræmer selected the inaugural members herself from among the prominent writers, scholars, and cultural figures of the time. Some of them she had been in contact with previously, as she continued to take an interest in current developments within the field of literature right up until the end of her life. She read and wrote, was an important figure in the women’s movement, and extended financial support to educational initiatives and poverty alleviation as well as to the great international congress for women’s suffrage in Stockholm in 1911.

Lotten von Kræmer died on 23 December 1912.

The Academy of the Nine

When Lotten von Kræmer’s will was read on Christmas Eve of 1912, the remarkable donation quickly made headlines across Sweden. Her fortune amounted to SEK 949,000 — which today corresponds to close to SEK 49 million (roughly $4.6 million or £3.8 million). As she had outlived all of her siblings, her eleven heirs consisted of their children as well as the children of a deceased niece. To these relatives, Lotten had bequeathed personal possessions of comparatively insignificant financial value, such as jewellery, clothes, fabrics, furniture, and household items.

Her relatives found the will impossible to accept. They soon filed a lawsuit against The Academy of the Nine, which had already been founded in February of 1913. The basis for the lawsuit was their argument that Lotten von Kræmer had not been in her right mind when she signed her will. It made little difference that, as a testator, she’d had the foresight to suspect that the will might arouse resentment among her relatives. In the summer of 1910, Lotten had hired two highly regarded psychiatrists and received a statement to attest that her mental health was intact. She also preempted any objections with a simple plea in her will, describing the plans as an expression of her long-standing ‘dreams and purposes’. Nevertheless, her relatives saw to it that the will became a legal matter, and a gruelling and protracted conflict ensued. It ended in a settlement that awarded the relatives a significant portion of her legacy.

Only then could The Academy of the Nine begin its work. Lotten von Kræmer had personally appointed the inaugural members, who offer an indication of her literary and cultural interests and liberal ideals. As chairperson, she appointed Prince Eugen, who would bring royal glory and was himself a recognised painter. Selma Lagerlöf and Ellen Key were world-famous writers, peace activists, and advocates for women’s suffrage — in addition, Lagerlöf had been the 1909 Nobel laureate in literature. Karl Wåhlin was an art critic and journal editor; the art historian Georg Göthe was a curator at the National Museum of Fine Arts in Stockholm. Kerstin Hård af Segerstad was a French literary scholar and involved in the fight for women’s suffrage. Göran Björkman was a translator who had written his doctoral thesis on Portuguese poetry and worked at the Swedish Academy’s Nobel Institute. The author and public educator Anna Maria Roos wrote poetry, children’s literature, and textbooks. John Landquist was a scholar of philosophy and an influential literary critic.

Two of the chosen members — Prince Eugen and Georg Göthe — declined and were replaced by the lawyer Viktor Almquist and the left-wing radical writer and editor Erik Hedén.

In June of 1913, The Academy of the Nine adopted its statutes in accordance with the will of the testator. In the statutes, the numerical equality between the sexes was formalised. So was the misson to award prizes to Swedish works of fiction, with the addition that non-fiction and translations of high literary merit would also be eligible. Otherwise, the Academy’s most important tasks were — in accordance with the instructions provided in the will — to publish a journal as well as a biography of the founder and beautiful editions of her writings. In 1918, the academy published her Samlade skrifter (‘Collected writings’) vol. 1–4, prefaced by a biography written by member John Landquist. The Academy has also published several journals and yearbooks: Vår Tid (‘Our time’) 1916–1930 (with a hiatus in 1926–1929), Svensk litteraturtidskrift (‘Swedish literary review’) 1938–1983, and De Nio. Litterär kalender (‘The Nine: a literary calendar’) 2003–now.

Lotten von Kræmer donated her house on Villagatan 14 to The Academy of the Nine, and its meetings are still held there today. The inaugural prizes were awarded in the spring of 1916, to six men and three women.

The members of ‘the Nine’ are elected for life, though it is possible to leave the Academy. Most members have been active for a long time and made significant contributions, some for as long as four or five decades. Over the years, a number of prominent writers, scholars, and critics have held a chair in the Academy of the Nine. Renowned names from the past include Stina Aronson, Karin Boye, Hjalmar Gullberg, Olle Holmberg, Ellen Key, Selma Lagerlöf, Sara Lidman, Astrid Lindgren, Birgitta Trotzig, Karl Vennberg, and Elin Wägner. Kerstin Ekman was a long-standing member and left the Academy in 2021.

Today, ‘the Nine’ usually meet four times a year. For some time, the Academy has also organised cultural events on Villagatan, including author talks, readings, and live music.

Over the years, The Academy of the Nine has presented a number of different prizes, several named after former members and some specifically dedicated to non-fiction. The Lotten von Kræmer Prize is awarded once a year, as is the so-called Grand Prize, which in 2022 amounted to SEK 400,000 (circa $38,000 or £32,000). The Christmas prizes in December are often awarded to early-career authors.

Until the Academy’s centenary in 2013, approximately two thirds of the recipients were men and one third women, according to Inge Jonsson’s history Samfundet De Nio 1913–2013 (‘The Academy of the Nine 1913–2013’). As he points out, these figures reflect a development over the course of a century and show a gradual ‘increase [of women recipients] over time’. In the years that have passed since its publication (2014–2022), prizes have been awarded equally to men and women.

Today, as in the past, the members of The Academy of the Nine are writers, critics, and academics. At the time of writing, the members are (in alphabetical order): Nina Burton, Jonas Ellerström, Madeleine Gustafsson, Gunnar Harding, Marie Lundquist, Niklas Rådström, Sara Stridsberg, Johan Svedjedal, and Anna Williams (chairperson).